Low cost, high-impact technologies designed to serve rural, off-grid places - BP monitors, mobile data monitoring platforms - are being used in developing countries to collect data on outcomes, connect patients with doctors and nurses, and provide a vital link between advanced care clinics and underserved populations. Such mobile health, or “mhealth” tools are often introduced in regions and cities where cell phones and smartphones are already ubiquitous, thus turning a global communication tool into a device for assessing and understanding everything from communicable diseases to family planning and eye care.

Concurrently, health organizations operating in rural, underserved areas often employ teams of community healthcare workers (CHWs): employees who are often from the communities they serve trained to educate their patients about ways to prevent and manage disease, use contraception, improve their diets, and more.

What have organizations that have combined these two models learned along the way? What might their experiences training and empowering CHWs to use mhealth tech teach us about how solution developers and healthcare providers can improve and scale services for people living at the bottom of the pyramid? And what do such organizations need to do in order to improve their work, that mhealth technology has yet to deliver?

We interviewed three organizations working to improve healthcare delivery for rural populations: iKure Techsoft Pvt. Ltd based in Kolkata, India; Possible Health, which works in Nepal; and Muso, which works in Mali and whose team answered questions over email.

Muso is a global health organization founded in 2005 with a mission to “eliminate preventable deaths that are rooted in poverty.” It relies on CHWs to provide a “proactive” healthcare model, including door-to-door visits and in-home services for women and children in Mali. Muso partners with Medic Mobile, a nonprofit that specializes in mhealth technology, to deploy solutions designed to help increase the efficiency and effectiveness of CHWs.

The Muso team wrote that Medic Mobile provides solutions that support the work of CHWs working on child and maternal health, health outcomes, and universal coverage. Medic Mobile’s solutions for CHWs include an app for smartphones developed through a process of human-centered design.

“Rather than adding work or additional tasks for CHWs, the App is designed to make it easier for CHWs to do their core work of transforming health in their communities,” the team at Muso wrote. “This free, open-source tool has the potential to scale in Mali and globally because it helps CHWs solve some of the most difficult challenges they face in their jobs.”

Muso explained that the app helps CHWs efficiently collect and report data and manage patient panels and tasks, ultimately allowing health workers to organize large numbers of patients while tracking care for a wide variety of health conditions across groups. The Malian Ministry of Health is currently partnering with Muso to evaluate the feasibility of scaling such low-cost technologies nationally.

Muso is also working with Medic Mobile to develop a new tool for its 360 Supervision Model, an initiative for mentoring CHWs and improving efficiency and quality of care. The CHW Dashboard - an internet-based platform for analyzing data - will support supervisors as they provide CHWs with individualized feedback on their performance.

“Muso will soon publish a randomized controlled trial on the CHW Dashboard, testing if supervision with mobile health tools helps CHWs continuously improve the quality, speed, and quantity of services they provide,” the team wrote.

If Muso is able to demonstrate whether and how these technologies developed in partnership with Medic Mobile improve the quality and equity of care, then they will be well-positioned for scaling by the Malian Ministry of Health, integration in Medic Mobile’s own quickly growing network of CHWs, and distribution through other governments and organizations working in Africa and Asia.

“Our relationships with leaders at global institutions will provide avenues for technological innovations incubated through this partnership to change global practice,” the team wrote.

Possible Health is another healthcare provider working with a national government to provide care for underserved populations. As Anant Raul, Healthcare Systems Engineer for Posible Health, describes, these facilities and CHWs work in tandem to “provide home-to-hospital care and create a population-level impact” in Nepal.

Possible Health uses digital tools to help deliver evidence-based protocolized and longitudinal care to detect epidemics. CHWs travel to communities equipped with Commcare, a mobile data platform developed by Dimagi. Possible Health’s Community Healthcare Team uses Commcare to address reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health (RMNCH). Commcare includes mhealth programs that help the Community Healthcare Team monitor pregnancies and toddlers, counsel patients with chronic disease, follow up with patients who have had surgery, advise on nutrition, and provide antenatal and postnatal care.

At the administrative level, Possible Health’s facilities store and provide data on patients with a variety of serious conditions, including high-risk pregnancies, chronic diseases, and malnutrition. CHWs, in turn, visit households in Possible Health’s catchment areas every three months. CHWs are able to sync data collected during these visits with servers at the facilities using mobile data networks or wireless networks. Patients’ data can then be downloaded and reviewed with Possible Health’s Community Healthcare Team, which makes programmatic decisions. Thus a cycle of care and learning involving Possible Health’s CHWs and facilities continues.

Raul wrote that quickly training CHWs to use mhealth technologies such as Commcare has allowed the organization to expand its services to new, previously hard-to-reach places in Nepal.

“We have successfully expanded to multiple municipalities in the last year without major issues, he wrote. “When rolling out the Community Healthcare Program in the new district, training the CHWs on the tools (which walk you through each care module) helped roll out the programs much quicker.”

Raul wrote that Possible Health is working on two areas in its operations involving mhealth tech: data visualizations for its CHWs, supervisors, and administrators and the syncing of data between the facility EHR and Commcare.

iKure Techsoft Pvt. Ltd. of Kolkata provides a variety of services in several rural regions in India, including general care, maternal and child care and disease prevention and management. Its “hub and spoke” model includes physical clinics where specialists receive patients and data is stored. This system of clinics includes the “hubs:” larger, centralized facilities housing specialists and data storage. iKure’s “spokes” include both smaller clinics providing more localized care and teams of CHWs, who meet with patients in their communities. iKure’s hubs house a unique cloud-based software called Wireless Health Incident Monitoring Systems (WHIMS), which allows these facilities and CHWs to work in unison, connecting the best of iKure’s services with patients in rural places, where intensive, specialized care can be hard to come by.

“Basically there are lots of challenges in rural places when it comes to health,” said analyst Tirumala Santra Mandal.

That’s one reason that iKure Techsoft relies on its CHWs supplied with point-of-care technologies to consult with patients, diagnose conditions, and collect data in what iKure’s Founder and CEO Sujay Santra terms “pockets:” places where people live without amenities such as electricity. The “hub and spoke” model currently costs each patient living in pockets no more than 10 rupees per person per month.

iKure selects its own CHWs, most of whom are women. The CHWs train for two to three months before they are deployed to the “pockets” with smartphones. Santra said that learning to effectively train CHWs to use smartphone technologies has been one of the greatest challenges the organization has faced thus far.

Santra describes how iKure serves clients in the state of West Bengal, which is home to over 9 Crore population. iKure’s “hub” facility allows patients to consult with doctors and receive medicines. Concurrently, mobile medical teams go deep into pockets to meet with villagers. These CHWs check vital signs and run general check-ups. Of every 50 patients, roughly 7 to 19 will need additional follow-up. CHWs use smartphones to upload data from the visits to WHIMs, which can be accessed from the field using just 2G and 3G networks.

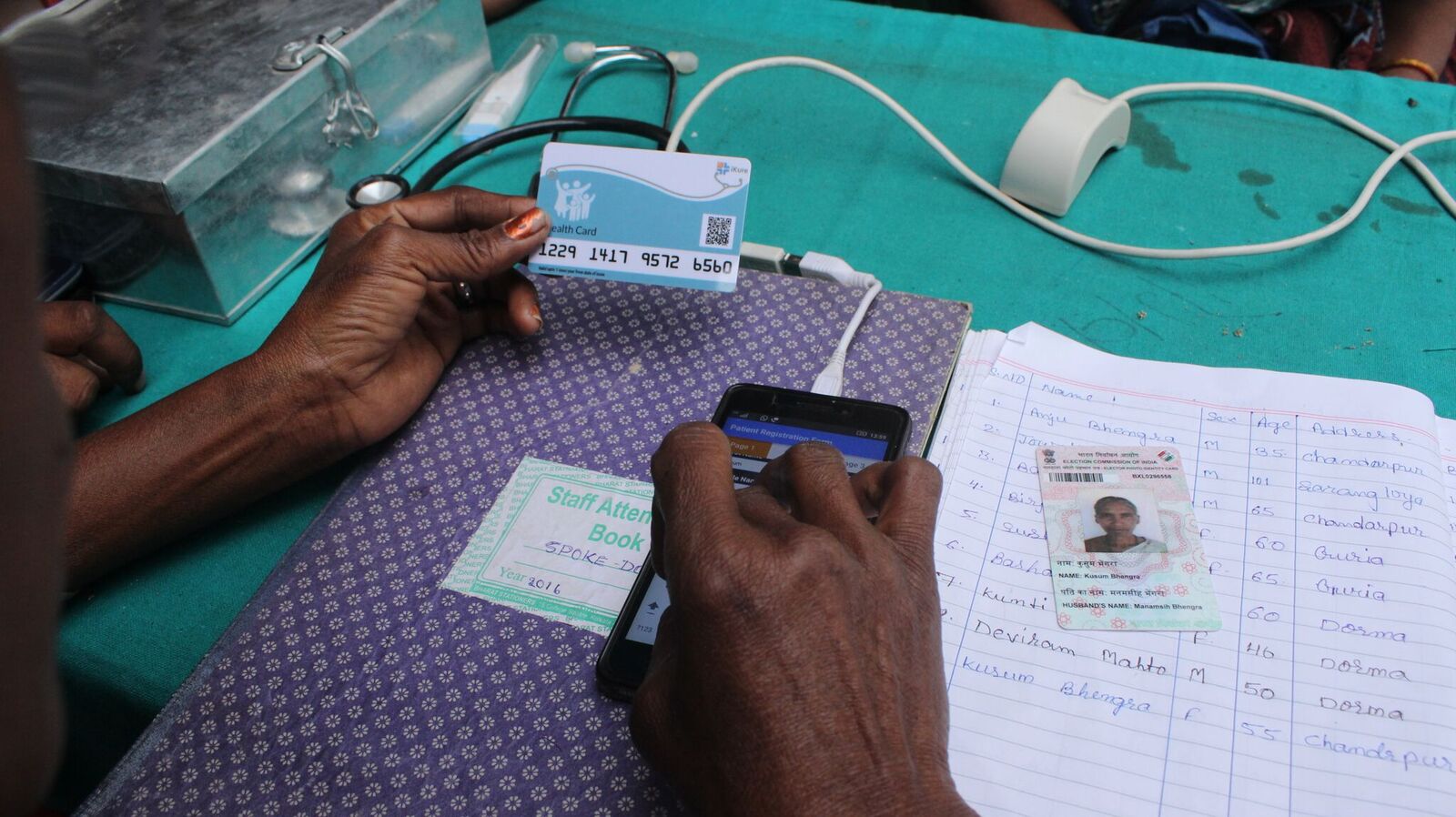

These CHWs also provide patients with iKure’s unique “digital cards.” Each card is encrypted with a QR code that connects the patient to WHIMS. Each patient pays an annual fee between 600 and 700 rupees to maintain this access to iKure’s system. These cards help iKure’s teams to record visits, monitor patients’ risk factors, and remind patients to take medications. In total, iKure’s ability to distribute digital cards via CHWs allows for what Santra calls “a continuity of care.”

iKure also partners with other organizations to broaden its impact. Currently, it partners with local organizations to provide more specialized care. It also works with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to identify non-communicable diseases such as diabetes in the hopes of finding ways to monitor and manage chronically ill patients over a longer period of time.

Looking ahead, iKure is considering new ways to provide quality, low-cost health services in pockets; it may even begin offering a subscription healthcare package to university students, whose payments could help subsidize the cost of providing care to lower income patients. Santra also described various ways that improved mhealth technologies could help iKure reach more patients.

“A couple of [mhealth] devices are quite costly at $5,000. We would need $500 devices for the services to become sustainable,” Santra said. “We are trying to add wallets to health cards. We are trying to introduce customized technology, i.e. blockchains. We want to be able to monitor and track our CHWs, but our current GPS technology does not fully allow it. There are new devices using mobile tech that could extend our health facilities.” Santra hopes that iKure will be able to tackle additional diseases as it strives to reach more patients in India.

“As we are able to build a strong framework across six states, we know there are a lot of oral cancer prevalence. We want to educate on early signs.”